In the Spirit of the Gracious and Compassionate

Creator of the Heavens and the Earth

The praise belongs to Allah.

When I was five, I started taking piano lessons. I was anxious to practice. Every day, I rushed home from school to practice. On cold wintry days, I dunked my hands in hot water because I couldn’t wait for my fingers to thaw out. I was really serious about playing the piano.

When I was seven, the World Book Encyclopedia arrived at our house. Mom and Dad had bought it for my older brother, but I was there when two workmen brought this big box into the house and opened it. The box was barely open when I began grabbing the deep maroon volumes and reading them. By the time I was twelve, all of the pages were yellow from use. If anyone who knew me wanted to give me a present, they gave me a book. I was really serious about learning.

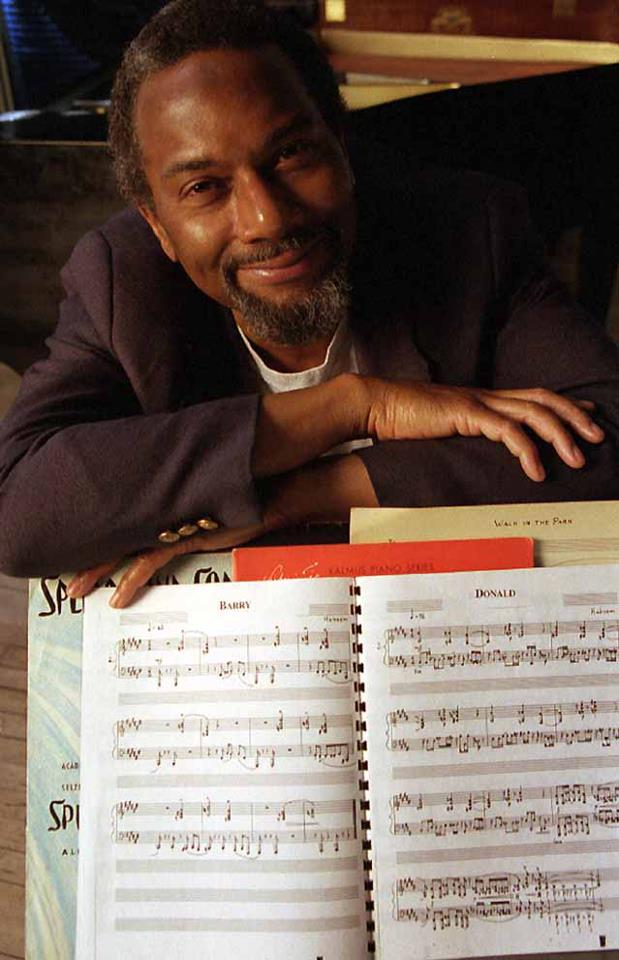

When I was nine, I began composing music. I studied music theory, and the works of Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Mendelssohn, Debussy, Mozart, and Khachaturian. As a teenager I consumed books on the technique of music composition. I was really serious about composing.

I went to the High School of Music & Art (now the LaGuardia School of the Arts). I played Mendelssohn’s “Venetian Boat Song #2” for my audition. I was taking piano lessons outside of school (with Dr. Eileen Southern), and winning awards. I’ve lost the copies of my awards, but I’m fairly certain I won at least one Local, State, or National award from the Piano Guild of the American College of Musicians, before winning two International Awards before my 17th birthday.

When I was 14, I wrote a “Prelude on the School Song” for woodwind quintet, which was performed on educational television (Channel 13 in New York City). (The school song — “Now Upward in Wonder” — used the theme from the last movement of Brahms’ first symphony as its melody.) I wrote a short “Toccata” for piano, and realized that I had finally found the musical language I had been looking for since I was a young child. When I was 15, I wrote my “Toccata No. 2” for piano, an excellent composition, which I consider the best of my (admittedly few) compositions. At graduation, I shared the Composition Award with another student.

A few weeks before graduation, I was one of several New York City high school students featured on a segment of the CBS TV show “Eye on New York” with Harry Reasoner.

In 1962, at the age of 16, I was admitted to Harvard University as a “Harvard National Scholar” — one of the top 50 freshmen in a class of 1,200 students. Based on my Toccata No. 2, I was admitted into the graduate seminar in composition. I dropped out after six weeks because of personal difficulties, but returned two years later. I graduated from Harvard College in 1968, cum laude (with honors).

Harvard was anxious for me to enter the newly established doctorate in music composition, and I was happy to oblige — so happy that I accidentally skipped the master’s degree. It was not until March of the following year — when my advisor asked me when I was going to start preparing for my Ph.D. oral exams — that I realized I was in a Ph.D. program.

I was a Graduate Prize Fellow, tuition fully-paid, plus a stipend that was enough to live on.

I had few courses to take. I had taken most of the graduate-level courses as an undergraduate. I found out that I could register for “Time”. The standard course-load was four courses. One-quarter Time stood in for one course, one-half Time for two courses. By the end of my second year, I was registered for Full Time — taking not one single course, while being considered a full-time graduate student and continuing to receive my fellowship money.

I had two particularly memorable experiences in graduate school:

- The first was when I was giving a presentation in a seminar on musical analysis. Each of the students was required to give a two-hour presentation on Arnold Schoenberg‘s String Trio — a supremely awesome composition, awesome in its technical brilliance, and also awesomely ugly and depressing; I hated it and admired it, at the same time. As a serious composer and analyst, I knew I didn’t need to love the piece in order to analyze it.

The morning of my presentation, I prepared a six-page outline, each page consisting of four points, each supported by a paragraph listing the measure number of musical examples. After the first half-hour of my presentation, I noticed that I had covered only the first point on the first page. At that rate, it would take me 12 hours to finish my presentation. So, I began to skip. Predictably, one of the other students challenged me. He said I was making points without supporting them with examples. In response, I repeated the point I had just made and, rapid fire, played on the piano several examples supporting that point. The poor man slid out of his chair. (When he had finished sliding, the back of his head was at the edge of the seat.) The other students gasped. Professor Kim (Korean-American, from California) beamed. In the following days, I discovered that the word “buzz” is literal. When I walked in the halls of the music building, there was an audible buzz. They were talking about me. - The second was in the final exam of a musicology course. Musicology was not my field, and I was always in awe of the musicology students — mastering such a technical and complex subject. For the first half of the course on music notation from 1450 to 1600 (before the system of notation used to this day took hold), I was stumbling. The textbook was thick — at least 800 pages — and the material was difficult to understand and remember. Then one day, it dawned on me: Don’t memorize the rules; learn to read the music. So I learned to read the old notation, and after that it was a breeze.

The final exams at Harvard all followed the same schedule. They were three hours long. No one was allowed to leave the room before the first hour-and-a-half, at which point there was a short break. At that point, no one was allowed to enter the room. If you were 90 minutes late, you missed the exam — a big no-no at Harvard. This particular exam was an open-book exam. We were given examples of 15th and 16th century music and required to transcribe them into modern notation. I looked at the musical examples and transcribed them. I never opened the book. It was a small class, and we were all sitting around one large table. All of the other students were busy consulting the book. As best I could tell, I had finished the exam in a little over an hour. That couldn’t be! I must have missed something. Desperately, I pored over the exam questions again and again. What did I miss? I couldn’t figure it out. Finally, when I caught my eyes wandering over to look at another student’s work, I decided to give up. I sat there for the remaining 15 minutes — until the first 90 minutes were up — then handed in my exam paper and left the room.

Lonely and desolate, I wandered around in the hallway, wondering what I did wrong. A few minutes later, the professor came up to me and said, “If Harvard allowed us to give an A-plus, I would give you an A-plus, but I can only give you an A.” I had aced the final exam in less than 90 minutes without even opening the book, while the musicology students were still poring over the book, looking for answers.

At the end of my first year, I moved out of Cambridge and over to Roxbury — the predominantly African American area of Boston. I had spent the previous 12 years associating almost entirely with white people, and suddenly I had had enough. In Roxbury, I joined the local YMCA and exercised there. And I took up African dance, ballet (because it was required) and African drumming at the National Center for Afro-American Artists (known affectionately as the “Elma Lewis School”). I was able to study African drumming with the esteemed Babatunde Olatunji free of charge, because men and boys were allowed to attend classes at the Elma Lewis School tuition-free. Women and girls were required to pay. (I assume this was because it was difficult getting men and boys to take “cultural” courses. As it was, all but one of the males in the dance classes were gay.) A few years earlier — I believe it was the summer after freshman year — I had taken a few dance classes with Gus Solomons, Jr.

Towards the end of my second year of graduate school, I was offered a position as assistant professor at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. I could have chosen to spend the next two years of my five-year fellowship as a teaching assistant (for little over $2,000 per year) — this was required — or accept the position at Antioch (paying over $9,000 per year, good money in those days). I accepted the position at Antioch.

For more about me, visit https://www.doctorhakeem.com/hakeemface.html. In time, I may actual write “A Serious Life – Part Two”.

By the way, if you are any of these things – a human being, an African American, a Muslim – I am your Brother.

My name is Lester.

17 Dhul-Hijjah 1441 / 28 Dhul-Hijjah 1441

August 7, 2020 / July 8, 2021