Ts’ai Lun and Your World

Ts’ai Lun is the seventh most influential person in history (according to Michael H. Hart, The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History). You’ve probably never heard of him. He invented paper. He was Chinese. If the inventor of paper had been European – a “white” man – we would have been learning his name in elementary school.

Ts’ai Lun lived from about 50 CE to about 121 CE. He invented the process for making paper in 105 CE.

As you may know, writing was invented thousands of years earlier. So, what did people write on? In China, they wrote on bamboo and silk. Bamboo is bulky, and silk is expensive. Further west, they wrote on wood, animal skins (which could be processed into parchment and vellum), papyrus (made from flattened papyrus leaves), bones, and stone.

These materials have the drawbacks of being bulky (all of them, except silk), fragile (papyrus), uneven (most of them), or expensive (parchment and vellum). Papyrus could be made into scrolls, but not into anything resembling a book.

Of all these materials, only parchment and vellum are suitable for making books. But they are expensive. A single copy of a 100-page parchment book might require the skins of 100 sheep. Vellum is a more expensive, higher quality form of parchment, made from the skins of baby animals.

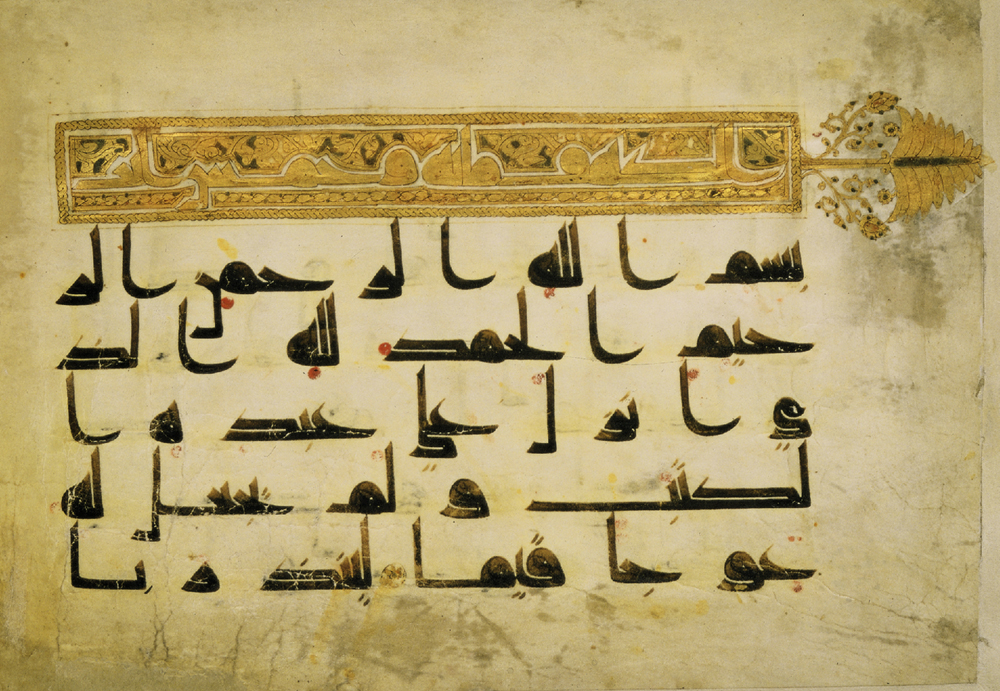

Paper was a major factor in the advance of Chinese civilization over the next several centuries. For several centuries, the process for making paper was unknown outside of China. In 751 CE, at the Battle of Talas River (north of modern Afghanistan), an Arab Muslim army met and defeated a coalition force under Chinese leadership. Captured in the battle were several Chinese who had knowledge of paper-making. As a result, paper-making – although it remained a state secret – spread through Muslim territories further west and eventually, four centuries later, reached Europe.

Nowadays, we are accustomed to an invention spreading across the globe within months, not centuries. We tend to assume that if paper was invented in China in 105 CE that paper would be known and used in Arabia by 570 CE, the year in which Muhammad, the Messenger of Allah (Peace and Blessings be upon him), was born. Not so.

Paper was unknown in Arabia at that time and for almost two centuries afterward.

It is widely believed that the Qur’an – which was presented to the world by Prophet Muhammad between 611 and 632 CE – is based on the Bible. Among the factors undermining this belief – such as the illiteracy of most Arabs, including Muhammad, the rarity of Christians living in central Arabia (and none allowed in Makkah), the absence of Jews in Makkah, the absence of libraries, and the scarcity of books – is the absence of paper.

In order to influence the Qur’an, the Bible would have had to be present either in memory or in physical form.

Whatever physical forms the biblical scriptures may have taken, they could not have been the compact, portable and convenient Bibles we are so familiar with today. Even if Prophet Muhammad had been able to read – not only Arabic, but also Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, Syriac, Latin and Ge’ez (the biblical language of Ethiopia), in which the biblical scriptures were written – where would he have found a bulky and expensive collection of scriptures to study? Where would he have found a person, or people, with an extensive knowledge of the biblical scripture?

Prophet Muhammad lived in a small town, Makkah, in the midst of the Arabian desert. At the age of twelve and as a young teenager, he made his only journeys – with caravans – outside of Arabia. He learned to be a successful and respected businessman. He was not studying scripture. He couldn’t read. He had no time to sit with learned men and study. And, there was no handy and convenient form of Bible that he could carry with him on his journeys.

No paper – no Bible as we know it today.

Even today, in this highly literate and overwhelmingly Christian and Jewish nation, we find only spotty knowledge in the general population of what is actually in the Bible. Imagine the situation in a small ignorant, illiterate and pagan town in ancient Arabia.

With no paper.

Sources:

Bucaille, Maurice. The Bible, the Qur’an and Science: The Holy Scriptures Examined in the Light of Modern Knowledge. Indianapolis: American Trust Publications, 1978

Fatoohi, Louay. The Mystery of the Historical Jesus: The Messiah in the Qur’an, the Bible, and Historical Sources. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Book Trust, 2009

Hart, Michael A. The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History (Revised and Updated). New York: Kensington Publishing Corp., 1992